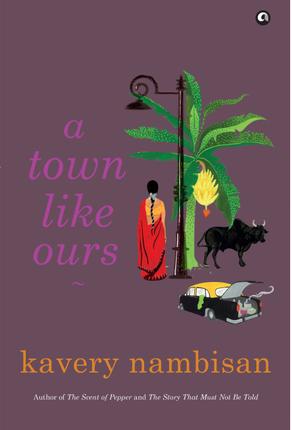

Kavery Nambisan talks to the writer about her book A Town Like Ours, and juggling the roles of writer and surgeon.

Pingakshipura — where the hair on children’s head has turned white and the water runs black — is the town Kavery Nambisan created in her latest book, A Town Like Ours. Though a fictional account of a fictitious place, Nambisan’s words resonate with a dark, uncensored truth that brings to mind the fate of hundreds of villages across the country. Known for her highly perceptive and emotive style, Nambisan talks about her writing and her dual life as author and surgeon.

Excerpts from an interview:

Tell us a little about how you created Pingakshipura.

It grew around the character of Rajakumari. When I created this endearing, coarse-tongued prostitute and tried to imagine her life, the place that came to mind was a shapeless, noisy pell-mell town. I worked backwards from the town to what it must have been a decade or two earlier. I thought I had created Pingakshipura but, in actual fact, it was like the villages of Karnataka where I lived in my childhood that, over the decades, transmogrified into towns. The lopsided modernisation that we so timidly endorse in our greed for wealth leads to a distortion of the intrinsic fabric of society. The deep and abiding wisdom that is a part of village life is forever lost.

You choose to use Rajkumari to tell the story?

She is derived from a real characterYou know how you come across a person and she stays in your mind and cooks away in your imagination until she is no longer a strangerThe important thing about Rajakumari is not her beauty but her ability to think, and to believe in herself. Her unique position as a harlot gives her the fearlessness and the freedom to retain her dignity at all times.

As for using her voice to tell the story, who better than a whore to give an honest account of the goings-on in any place, who better to tease out the absurdities of life and people? Her voice is like the drumbeat of Pingakshipura, the collective voice of the town. She speaks in her language, namely Kannada which is also the language I grew up with in school.

Not every character’s story is resolved. This seems to be deliberate.

It is Rajakumari who speaks. She is keenly interested in the lives of four people; two couples and two children. My own experience is that the lives of seemingly disparate people come together due to the strangest of circumstances. And a novel is only a peeping-hole into something that happens somewhere. Life can be a charming fairy-tale but more often it is a mess. I look in and show what I see.

I am also very interested in the way we keep secrets from each other, the way we speak half-truths and get away with it all the time. We try to shield our own ‘imagined’ dignity or shield that of others. But see what dilemmas we can end up with. Would it not have been easier for Manohar to tell his wife about his longing for children instead of doing what he did? Or for Saroja to be utterly honest with Sampathu?

A Town like Ours seems to underline your own worries about where rural India is headed.

I guess that runs like a theme through the book, although it is not talked about much. Yes, I am depressed about the destruction, the thinning away, of our link with Nature. It is like humanity is steadily losing blood, getting more anaemic by the day and, instead of treating the cause, is trying to pep itself up by using the magic tablet of modernisation.

Is this the kind of fiction you believe in writing, one that reflects on and mirrors reality?

I did not plan anything. When I started, all I knew about writing was that you had to tell a story. I like stories that make me smile or laugh (sometimes with bitterness). But what really moves me is the grand canvas of living. We humans have a greater capacity for grief than for joy, don’t you think? At least, that is the case with me. I try to be honest, that’s what I do when I write. Everything flows from there. Injustice of all sorts fills me with disbelief about our future and I write so I can change that disbelief into something more hopeful.

Are there any similarities/overlaps in the two facets of your life: writer and surgeon?

Surgery is all about knowledge, skill and team-work. Writing, on the other hand, is done in isolation; it is a bizarre mix of observation, experience, memory and imagination, a chipping- away until something comes out on the page. But both writing and surgery require a certain confidence and the ability to take risks. Who knows what your novel will turn out to be like? In surgery, the risk is that each human body behaves differently and, although you think you know it well, it always throws up surprises. When I open an abdomen, or take on something else, I should be prepared to handle the innumerable variations. Especially in a rural area where you cannot cry for help. You succeed by staying abreast of progress, by keeping your faculties sharp and your mind open to learning. Once you say, “Yes, I can do this for you,” to a patient, you go all the way in the best way possible. By nature, I’m a risk-taker. That’s how I’ve survived as a writer and a surgeon.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> Sunday Magazine> The Sunday Interview / by Swati Dastur / August 02nd, 2014