Spot on in bringing characters alive.

In literature that delves into social miseries, there is a common feeling that those who have words don’t have the stories, and those who have stories don’t have the words. If you’re living on the pavement with your family, you probably don’t have the means to record the experience for posterity. On the other hand, if you sit at a desk of your own and compose literature, you don’t have access to the miseries you want to write about.

To reconcile that problem, writers set up a peculiar kind of narrator, the person steeped in the rough life who somehow has the vocabulary and wider perspective to tell the stories. It is the kind of construct we find in old fiction, like Nelly Dean from Wuthering Heights or the flamboyantly criminal Moll Flanders. Nowadays, it seems an unnecessarily elaborate way to get to the stories. Readers are primed to accept them without that explanatory frame.

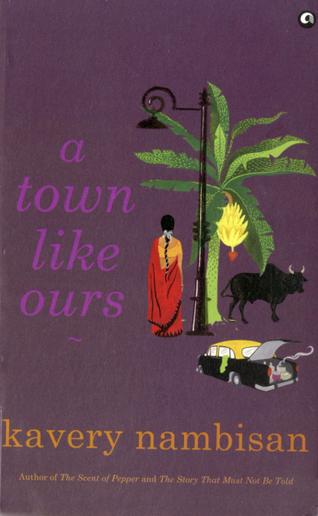

In Kavery Nambisan’s A Town Like Ours, the peculiar narrator is Rajakumari, a retired prostitute who lives in a dark room somewhere in the temple of the village goddess. She knows everyone’s back story and is not ashamed to tell it all. In her early years, she was enterprising enough to trade sex for lessons in maths, language, anatomy and other subjects. With education comes some preachiness, but we are Indians and that’s how we spin a fiction. Rajakumari has plenty to say about the chief industry of the town, the way it has poisoned the wells, contaminated the soil and whitened the children’s hair. She opines on religion and knee joints. But mostly she studies human nature. Old acquaintances come to visit, women come to confide their sorrows, and young boys help her walk to the sanctum of the goddess. Through her tiny window, she reads the faces and gestures she sees on the basis of the many souls she has entertained in her working life, and she puts it all together.

At the centre of her stories is the family that lives out of an Ambassador taxi. Father drives it during the day, mother runs a tea-and-bajji stall out of the trunk after she comes home from her housecleaning jobs, the sister and brother go to school and spend the rest of their time on the streets. But there are in fact no brothers, sisters or fathers in the case. Saroja and Sampathu, each escaping a frightening past, have simply joined forces and are bringing up two children together. In spite of strong affections, the family is a fragile composite that holds together for some time and then fragments again. One child goes missing and then the other, and suddenly Sampathu is not to be seen.

Elsewhere in the town, Manohar and Kripa separate after a fight and come together again. This couple become enmeshed with Saroja and help to look for her family. Nambisan is spot on in drawing Saroja’s situation as the woman left behind. She cannot tell her neighbours she doesn’t know where the other three are. Every day she parries questions about when her husband is “coming back from the village”. She must keep up appearances, or she will be judged and found wanting.

Up to that point Nambisan’s novel is leisurely. We move back and forth through memories and conversations to find out what kind of person each character is. But the suddenly precipitous pace near the end throws us, as each member of the family comes wandering back and misunderstandings flower among them. The whore in the temple says a prayer for herself, and leaves us with unfinished stories.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Literary Review / by Latha Anantharaman / October 04th, 2014