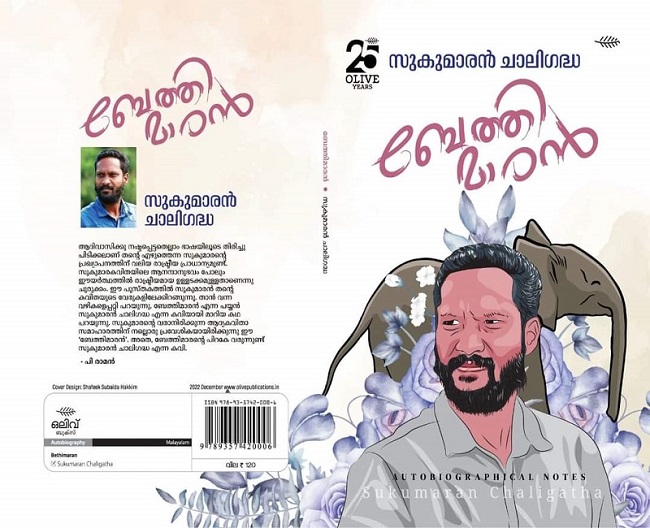

In this excerpt from his memoir, Sukumaran Chaligatha, a poet who belongs to the Adiya tribe, writes about his experience working in the ginger farms of Kodagu and the exploitation tribal workers faced.

The following is a chapter from poet Sukumaran Chaligatha’s memoir Bethimaran. The chapter, titled Kudannadili Bulenta Injimu Uganda Njathukkallumu (The Ginger Crop of Kodagu and Sustenance of Life), has been translated from Malayalam by Binu Karunakaran.

Like the Bengalis who migrate to Kerala consider the state their ‘Gulf’, the Kodagu district in Karnataka too was ‘Gulf’ for the residents of Wayanad, who were taken there for work in the ginger farms. The journey was compelling. From every ooru (tribal hamlet) they would take five to six jeep-loads of people – men, women and children – jam-packed like cattle. The children felt happy seeing the adults find work and travel because of them.

Most of the workers in the ginger farms of Kodagu were from Kerala. Landlords in Karnataka owned huge farms running into acres. Houses are located five kilometres from each other. The people who take the land on lease for cultivation have specific instructions for Malayali agents, that on this particular day, in a particular colony, you will find good workers.

Each person would have taken 20 to 30 acres of land on lease and would need five or six jeep-fulls of farm workers. We would board the jeeps at around 6 in the evening. If someone eats on the way, it would be noted down in an account book. When it was time for wage distribution, this amount would be deducted. Sometimes our wages were denied. If we needed money, an advance would be given.

Some workers would take Rs 500 as advance and then splurge Rs 300 on drinks. Whatever is left would be shared with the family to meet expenses till the worker is back. One should remember that this money is meant to last the next one or two months. While returning, what remains would be the overhead of credit against one’s name in the ledger. Sometimes we would be told that money is due to them.

The jeeps would reach Kodagu late in the night. The men would be dead drunk by then. Sighting of elephants and bison was common and the front seats of the jeeps were in demand because of this. There would never be enough seats and many would hang on to the rear throughout the journey. We would reach by 2 am and there was no option but to sleep on the ground.

In the morning, the workers themselves would have to build the shed in which they would stay. It was no better than a large cattle shed, built by cutting trees in the farm and using them as poles. The roof was made of palm leaves and grass. The shed would have a kitchen, where two women would be assigned to cook rice gruel and curries. There would be a mesiri (mestri/head workman) to monitor the workers. He would keep an accounts ledger.

The mesiri was entitled to a separate room inside the shed, where liquor was stored in white-coloured pouches called moolavettis (since the corners or moola of the pouches had to be cut to consume the liquor). Anyone who drank the stuff would spin like tops. It was nothing but plain spirit. Once opened, the packets were emptied straight into the mouth without mixing even a drop of water. The women would drink too. It was nothing like the liquor one gets in Kerala.

For men, the daily wage was Rs 75 and for women Rs 55. Each moolavetti was priced at Rs 3 or Rs 4. Men would polish off five or six packets in a day, the price of which would be cut from their daily wage. Apart from the moolavetti, there would be betel quid to chew too. Mesiri would write down everything in his ledger under various overheads. And the food? Rice gruel, rice, dried sardines, and a chutney made of chillies. The menu was the same every day. After the meal, one would have to work till 5 in the evening or 6. In the mornings, work would start at 7 or sometimes 6.

The mesiri would first arrange some workers to plough the field, then decide the date on which ginger is to be planted and take us. The process resembles a burial. Initially long beds are prepared by scooping up soil from two sides on which seed tubers are sown. There would be boys as young as 10 among the workers. They would keep sowing all day from small baskets filled with seeds, all under the fierce sun. The seeds are topped with soil and over it another layer of dried leaves and grass is added. Sprouts would appear in a month’s time. The beds need to be watered regularly.

The real danger, however, was the highly potent pesticide used in the ginger farms. From a single root, 5 or 6 kg of ginger can be obtained. Which is why pesticides are used excessively. If the price for a sack of ginger goes up by Rs 2,000 or Rs 3,000, they would be rich. I have heard old-timers sharing stories of people who became crorepatis by ginger farming. It’s like winning the lottery. For some people, cultivating ginger once is enough to make it big.

The seed tubers are kept immersed in pesticides in large pit-like tanks. Adivasi men, without any kind of safety gear, have to climb down these tanks to take out the seeds. Not even a glove is provided to take out the pesticide-coated seeds or while handling cow dung. When it’s time to eat, everyone washes their hands with a cake of soap. That’s the only safety they have. Tribal hamlets are rife with stories of people who died because of this lack of safety.

Workers are needed to dig trenches. Ten people would dig side-by-side as the work needs to be completed soon. Employers know how many people they need on a particular day. For Adivasis, the work is hellish. On top of that is the sexual harassment of women by the landlords and mesiris. These happenings are narrated as stories by those who have been to Kodagu, when they work in the fields back home. There have been instances where people have been killed when issues arise.

Once the work ends, the workers come back like kings. It’s as if they have returned from the Gulf.

When one planting phase is over, the men are sent back. After a while, weeds would start sprouting and to deal with this, women are hired. After that workers are again hired to build ledges. The ginger beds need to be filled with more soil and for that men are needed. For each phase, people are hired. When it’s time for harvest, men, women, and children are taken together. When it’s time to return, some would call from Kodagu and inform their dear ones they would be returning on such and such a date. Workers would wait with excitement if their return coincided with the Valliyoorkavu festival or with Onam. After all, they did not have much to do. On the day of return, they would be truly happy. The money they earned working for so long would be splurged in a single day. Nothing is saved. The men would spend the entire money on alcohol. Those days Adivasi men were heavily into drinking. The women would buy clothes and goods for the entire family. Then everyone would leave as a group to watch a movie. From a single colony, 10 jeeps would leave for Mananthavady. Some would go to Batheri. The ambience in the ooru would be festive. Absolutely no tension. The happiness of having returned to ooru after all the torture in Kodagu. On that day, anyone else would fail to get a seat in movie theatres in Mananthavady, Batheri or Pulpally. Everything would be booked by adivasis. If someone else enters the theatre and an altercation happens, adivasis would beat them up. Brawls would be endless and many blows would be exchanged.

When I was in Class 4, I remember listening to the stories of those who returned from Kodagu. The stories were amazing. The men would also sing songs, new songs that they had themselves made up. They spoke about places where you can fish and where the river was. It was a kind of knowledge that couldn’t be found elsewhere. I listened to these stories when studying in Class 4 and 5 and felt the urge to travel. When I told my father, he agreed. That my aunt and other family members were there too made it easier. Thus began my journeys traversing many kilometres. Do you know how many places in Karnataka I have been to? The journeys would end in big estates, places that are hard to reach, without access for vehicles. Calling out to a fellow human would often be futile as there would be no one to respond. These are the kinds of places that I worked. To live, one has to…

These were the only kind of jobs available for adivasis at that time. We have been continuously subjected to disdain for being adivasis. People could subject us to anything by spreading the idea that adivasis are not intelligent or resourceful, that there is no harm if they are threatened, beaten up or even killed. Adivasis would come and work. If we had behaved like them, there would have been no settlers in Wayanad today. Isn’t it because we were decent that they continue to live there. What if we were not so…? We became slaves when the settlers arrived. They became landlords.

I was a small child when I went to Kodagu for the first time. The wage fixed for me was Rs 5. I worked for more than two months. They owed me around Rs 800 for various kinds of tasks, but it was never given. They made me, a child, work, and then stole my money. I planted ginger seeds, I dug canals to drain water from the ginger beds. I ate rice gruel, chutney made of chillies, and dry sardines. None of us could breathe well because women, children, and men were forced to stay in a single room. And there were no toilets. We went outside, to a corner of the field to attend nature’s call. If the men fell sick, they drank a packet of arrack. Our hands never felt clean even if we took a bath, they would always look black-coloured. We learned this when comparing them with the rest of our body. How much ever we decked ourselves up, we were never clean. Our bodies and health underwent many changes. The slavery and torture we went through was never talked about in Kerala. Thinking about it even now fills us with sadness. Ithiyammas (grandmothers) would say: “We brought up 10 to 15 kids only for them to work for a single measure of rice.”

Some old-timers who went to work in Kodagu are still alive. Their bodies bear the marks of their experiences. I worked in ginger farms at a place called Hunsur till I turned 15. I was studying in Class 10 when I finally stopped working. The last time I went for slave work other than in ginger farms was at Shanivarashanthe in the Nagarahole area. It was many years later. A forested place with no human habitation. It was a time when I was jobless and had no money. The work assigned was to stand guard at cassava farms on the estate and keep away wild boars and elephants. We couldn’t speak, we were supposed to listen to whatever they told us. Sometimes they would beat us or shower us with swear words. We had to get up early. At times I was full of anger. They would wake us up at 5 am, sometimes at 3.30 am. Mesiri wouldn’t let us sleep. The reasoning was that only those who rise early work. The tasks we did were full of hardship. On some days I said that I won’t work marking it as leave. If you don’t work, there are no wages. Do you know the days I have worked despite being sick? Many, including women and children, have died. Our people did not realise that they were being exploited in Kodagu. Despite all this, our people used to sing secretly. It is through these songs that they rejuvenated themselves. I think all tribal people across the world, including Africa, would have done the same thing. They would have shared stories of their own and sang songs in between. There was no time to rest between work. No one would be allowed to even sit for five minutes after a meal. I wrote a film script titled Shanivarashanthe based on my experience.

A change came after government interventions in 2008. Many organisations took up the cause, visited the ginger farms in Kodagu, and made the reports public. It became news. People began to talk about these matters that were known but no one had bothered about till then. When adivasi organisations intervened, it became serious. It started affecting families and livelihoods. The government started to keep track of people travelling to Kodagu. The local police station was asked to keep a record of their names, phone numbers, and dates of leaving. Until then no one knew such details. People would be stuffed till the vehicles are full. The only document was the ledger kept by mesiris, which would have names. But it would be in their hands. Gradually, the police stopped intervening. Adivasis themselves stopped going for such work. The trips to Kodagu from tribal hamlets came to a stop.

I wrote a poem called ‘Soundless Tata’ based on the experiences in Kodagu. When it first appeared in print, I felt as if the history of Kodagu itself had been documented. The poem was first written in Ravula and then in Malayalam.

Soundless Tata

An Adivasi youth

went to Kodagu

and came back

having lost

his umbrella.

The notes he had,

five or eight

were all green.

The coins, a few

more, all white. Two

dhotis and two

shirts wrapped

in a cover from Geetha

Textiles, bath towel,

a warm blanket and in

his hand a packet

of mixture to snack.

Kids ran to him like

Usain Bolt.

The shy wife

closed her eyes, the hug

was like Dhritarashtra’s.

Mother-in-law had

more work to do

kitchen

courtyard

kitchen

courtyard

munching by kids

ogling by neighbours

ah, you’ve come…?

Having a blast

today, having a blast

tomorrow

Met everyone, need

to leave day after,

heap soil over ginger.

Got as advance Rs 500,

Rs 200 for the wife,

Rs 50 for mother-in-law,

candies for kids,

employer hasn’t

settled the dues, kids

still have their

candies, wife’s face

is all puffed up in anger.

The jeep has come

Kodagu, Kodagu…

Will be there for the festival.

Sukumaran Chaligatha is a poet who writes in Ravula, a tribal language, and in Malayalam. He is currently a general council member of the Kerala Sahitya Akademi and also the ooru mooppan (tribal chieftain) of Chaligatha near Kuruva Dweep in Wayanad. His memoir Bethimaran, published by Olive Books, can be purchased here.

source: http://www.thenewsminute.com / The News Minute / Home> News> Literature / by Sukumaran Chaligatha / June 14th, 2023