Featuring unique words and vowels not found elsewhere, the Kodava language, spoken in Kodagu, is an independent Dravidian language. According to the most recent data from the Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy, there were 21 castes living in Kodagu who spoke the Kodava language: the Kodavas, Amma Kodavas, Kodagu Heggades, Kembattis, Airis, Koyuvas, Boonepattas and the Gollas (Eimbokalas), to name a few.

Kodagu was an independent principality in South India between 1633 and 1834. After the British annexed Kodagu in 1834, it was called Coorg and became a province of British India. After Independence, Coorg was retained as a state and placed under a chief commissioner. In 1956, when the states of the Indian Union were reorganised, Coorg became a district of Karnataka state.

Kannada was the official language in Kodagu for much of its existence. The Kodava language generally uses the Kannada script.

The earliest inscriptions found in Kodagu date back to the 9th and 10th centuries and are in Kannada. But there were two peculiar 14th-century inscriptions of Kodagu, dated around 1370-1371 AD found in the Bhagandeshwara temple of Bhagamandala and the Mahalingeshwara temple of Palur. Many have dismissed the inscriptions as a mixture of scripts and languages. In 2021, my work involved isolating letters used in both. I labelled the script used ‘thirke’ (meaning ‘temple’).

Several scripts

There have been a number of scripts invented for the Kodava language in the last 150 years or so. Koravanda Appayya, a doctor in the erstwhile Mysore State, had invented one with around 50 letters in 1887.

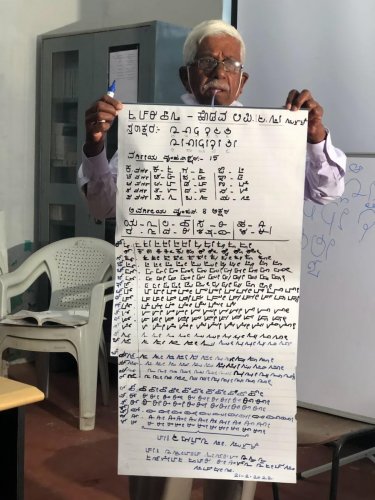

Kodagu scholar Iychettira M Muthanna invented another alphabet for the language in 1970. Appaneravanda Kiran Subbaiah, a sculptor in Mysuru, invented one in 1980. In 1983, he introduced a variant of the Kannada script to accommodate the Kodava language. Often, Kannada or Roman characters (the script used for English) were adapted, sometimes with additional changes.

Ponjanda S Appaiah, a professor, used the Roman script with his own transliteration system in 2003 to write in the Kodava language. In his Kodava-English dictionary, Appaiah used combinations of English letters for the Kodava language. He authored the entire book in the Roman script.

On the other hand, the ‘Kodava Arivole’ (Kodava dictionary) by Boverianda Uthaiah is in the Kannada script and makes use of 35 of the 49 Kannada letters.

In 2005, German linguist Gregg Cox introduced the Coorg-Cox script. Three years later, Charles Henry Kumar, a teacher from Mandya brought out another script to write the Kodava language.

Extra sounds

Boverianda Nanjamma and Chinnappa say that in addition to the five rounded Kannada vowels (with both long and short forms), the Kodava language has four unrounded vowels in their short and long forms and a nasal sound which accompanies some of the consonants. They have used five diacritical marks (symbols added above letters to indicate accent, tone and stress) in their works to accommodate these extra sounds.

In February 2022, under the presidentship of Ammatanda Parvathi Appaiah, the Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy discussed the various scripts used for the Kodava language. Bacharaniyanda Appanna, a former president of the academy, taught those assembled the script invented by I M Muthanna.

Upon comparison, it was declared that Muthanna’s script was the easiest to learn. The Kodava Sahitya Academy then recommended the Muthanna script to the Central Institute of Indian Languages to be made official.

Muthanna was of the opinion that his script was to be taught to children below the age of 15-16 years, says Appanna. “They will learn with passion and help promote the script when they write in it and inspire others,” he adds.

On why a script is important, Appanna says: “A script adds strength to a language, like how pillars strengthen a house. Yet, there are many prominent languages which do not have their own script. English uses Roman, Hindi uses Devanagari.” Having a native script is also important as it accommodates native sounds otherwise not found in other scripts.

Nerpanda Prathik Ponnanna, a language activist, has been popularising the Muthanna Kodava script by creating awareness about it through social media videos. He has also been getting signboards in the script for various shops, ancestral houses, and hockey tournament family teams.

source: http://www.deccanherald.com / Deccan Herald / Home> Spectrum / by Mookonda Kushalappa / May 10th, 2023