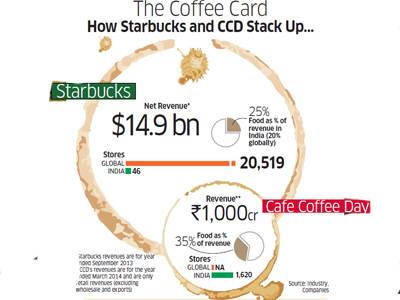

It is 5 pm on a weekday evening and the line at Starbucks in Indiabulls Finance Centre, a swish business complex in south Mumbai, is teeming with executives looking for their caffeine fix. With ties loosened and jackets casually slung over their arms, these men and women from the financial services, consumer goods and media firms housed in the towers of the complex are an ideal target audience for a range of beverages and snacks sold by Starbucks, the world’s largest coffee retailer; in 20 months of its inception in India — via a 50-50 joint venture with Tata Global Beverages — Starbucks has set up 46 such stores nationwide and has plans for dozens more.

Cut to Ulundurpet, far removed from the urbane chatter at Indiabulls. This town of some 400,000 people in southern Tamil Nadu is best known for being halfway between Chennai and Tiruchirappalli, an industrial and temple town some 320 km to the south. If Starbucks has embarked on its fastest-ever expansion globally in India, the homegrown leader Cafe Coffee Day (CCD) isn’t easily intimidated. India’s largest coffee retailer has launched some 150 stores in the past 12 months and plans a similar number in the next year. What’s more, it isn’t sticking to one format. In a bid to firm up its position, CCD has launched formats for malls, highways, an upscale offering called Lounge and a single-origin coffee destination called Square.

The world’s largest chain and India’s No. 1 retailer are squaring up for control of the country’s coffee retailing market.

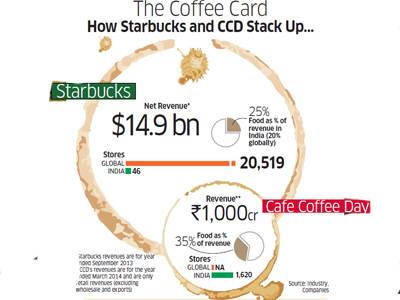

VG Siddhartha, the reticent founder of CCD, is all beans when he speaks to ET Magazine. “Our dream is to be among the top three retail coffee brands in the world,” he says. Already, CCD is present in some 200 towns across the country (it is often the first and only coffee retailer in many locations) and is aggressively expanding its footprint. “We hope to grow our retail business at about 20% in 2014-15 [and] we hope to do a revenue of Rs 1,200 crore from retail sales and another Rs 350 crore from the wholesale and export business this year.”

Siddhartha is firmly stepping on the gas with CCD. “We want to have around 2,500 Cafe and Express outlets in three years…we will set them up wherever there are opportunities, including at educational institutions, hospitals, expressways and high streets.”

Bean There, Done That

Siddhartha, who pioneered the bean-to-cup concept in the coffee industry — his Amalgamated Bean Coffee owns the plantations where coffee is grown and processed and later served at CCD outlets — is now set to take his next big step. According to reports, CCD has initiated plans for an initial public offering, which may value the chain at $1 billion and provide PE investors such as KKR an exit. CCD and its investors declined comment on the possibility of such an IPO.

A war chest from such an IPO will help Siddhartha finance what is quickly evolving into a two-horse race for India’s coffee cafe mart. India’s No. 1 chain, which has spent the past two decades building up its business — and has been predominately unchallenged — will face up to its strongest challenge yet. The $15-billion Starbucks is preparing to raid its citadel, digging its heels in for a long, bruising brawl.

Coffee, Anyone?

India is predominately a nation of tea drinkers, with most chains struggling to keep business afloat. Siddhartha opened the first CCD in 1996 on Bangalore’s Brigade Road, initially to serve pricey cups of coffee and let customers experience internet, then a novelty. While he opened the first store based on visiting a similar store in Singapore, the internet novelty wore off and CCD gradually became a beverage and food retailer.

Over the past two decades, CCD and other chains have been trying to persuade more people to visit their outlets and drink coffee. For all the coffee drinking claims, India remains a relative lightweight. Scandinavians throw back, by far, the most amounts of coffee and, across the world, several other countries such as the US and China swill vastly more coffee than India (see A Tea Country Still).

Since inception, CCD (and several other chains) have scaled up the coffee drinking experience from crowded non-airconditioned cafes to far more luxurious outlets, offering clean cutlery, a refined ambience and, increasingly, a growing assortment of food. Indians have willingly signed up, with industry estimates pegging this segment’s growth at about 20% annually.

The advent of CCD and later a plethora of chains targeting this free-spending consumer catalyzed coffee sales. “Domestic consumption of coffee, which was almost stagnant in the 1980s and 1990s, picked up an impressive pace in the past 7-8 years,” says Jawaid Akhtar, chairman, Coffee Board. “We estimate the domestic consumption at about 115,000 metric tonnes a year now which is growing at about 5% a year…driven largely by consumption through branded coffee chains.”

CCD and Starbucks are both wrestling for a share of this fast-growing market — and elbowing out the strugglers in their slugfest.

Risky Business

CCD’s Siddhartha will be the first to admit that running a cafe chain can be a bruising business. For starters, real estate costs have hobbled and humbled many of CCD’s rivals, who’ve struggled to make costly stores in central districts viable.

According to industry estimates, rentals can account for 15-25% of the cost of running a cafe chain. Then, there’s the investment in making a store appealing to customers with its interiors, finding people to run them and building a food and beverage menu that’s hip enough to keep 18-24-year-olds — the target market for coffee chains — coming back for more. CCD has tried to find a way around this problem by entering into a revenue-sharing deal, paying 10-20% of a unit’s proceeds as a fee. “Store location is a prime factor to consider for these chains,” says Reteesh Shukla, associate director, food and agriculture, with Technopak, a business consultancy. “Retail space is becoming very expensive, but you need to balance the ever-increasing costs of this prime real estate by being in [relatively less expensive] areas frequented by the youth.”

CCD has been successful in India because of its beanto-cup business strategy, which gives it control over bean production and processing and greater efficiency from its back-end set up. While Starbucks does have similar strengths thanks to its Tata tie-up, industry watchers say its relative lack of size in India means it’s at a disadvantage in squeezing out similar economies of scale. Opening a new store isn’t just about finding a good location and dressing it up for a brand-conscious a u d i -ence. Instead coffee chains need to figure out a tricky supply chain — how to get food and beverage to these outlets quickly, while keeping quality high.

The others, who don’t have this backward linkage, have predictably struggled.

While the opportunity may be tempting, food and beverage outlets are dealing with a soft market, where consumers are cutting down on how often they eat out and reducing how much they order when they do. For cafes such as CCD or Starbucks, this is a blessing in disguise — consumers are reducing their spend on full-scale restaurant meals and instead scaling it down to a coffee and a snack.

Starbucks’ Advent

Since he started his coffee chain, Siddhartha is facing up to perhaps his biggest challenge. Starbucks, which opened its first store in 1971 in Seattle’s Pike Market, today operates 20,519 stores globally. In the US, the chain has become a byword for a quick, upscale cuppa (not just coffee, but increasingly tea too, with Teavana Oprah Chai launched with talk show host Oprah Winfrey), with Alist celebs and executives all having their personal favourites. Starbucks has attracted thousands of loyal customers to its My Starbucks loyalty programme and has even worked with tech start-up Square to pilot cashless transactions at its stores.

While Starbucks has till recently focused on its home market, it has changed tack in the past few years. For example, it announced ambitious plans to scale up its presence in China — it will open 700-odd stores this year — even as it looked to manage tough economic headwinds. In October 2012, the firm announced a JV with the Tata Group to launch some 50 stores in India. While Starbucks thought of initially going it alone in India (foreign direct investments in single brand retailing are kosher) it decided to lean on Tata Global Beverages’ experience in the coffee industry supply chain to give it additional leverage here.

Expanding faster in China and then India is financially prudent for Starbucks. Starbucks’ operating margin for the second quarter of financial year 2014 (ended March) was 32.8% for the China Asia-Pacific segment, 21.6% for the Americas and 5.7% for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

While CCD had to build its brand from scratch in India, Starbucks hopes to leverage a globally familiar label with its target audience. When its first store opened in each city, winding queues were formed well before opening time. Familiar with its offerings in tall, grande and venti sizes, thanks to consumers who’d travelled overseas, either in real life or virtually, Starbucks’ India business got off to a rousing start.

Chinese Inspiration

Starbucks has shown some gumption going after opportunities overseas. For example, it has made a splash in the Chinese market, says Elizabeth Friend, an analyst with Euromonitor, a research and analysis firm. “Starbucks has done very well in a number of emerging markets…much of this has had to do with the brand’s very strong global reputation, which helped it to gain more immediate traction than other lesser-known chains,” she says.

“They’ve also done a really great job tailoring their brand — through store design, menu innovation and even learning how local stores are operated — to best suit each individual market.” In China, this has included leaning toward larger store footprints that offer space to relax with coffee in the afternoon. The addition of beverages such as the red-bean

frapuccino and a broader tea-based menu have helped Starbucks make strong inroads into the Chinese market, says Friend.

Starbucks’ rise in China may provide many lessons for its India business. In a large country Starbucks has had to localize its menu to keep customers coming in — something it has done quickly in India too, with dishes such as chicken tikka panini. Starbucks had cornered over two-thirds of the coffee cafe market in China until 2010, estimates Euromonitor, even if aggressive domestic rivals have more recently cut its market share to 60%.

Friend of Euromonitor says Starbucks has been able to replicate some of this success in India, too. “Some of India’s new outlet launches have been among Starbucks’ most successful in its history,” she claims. “Starbucks has been steadily gaining on local leader Cafe Coffee Day, though the chain will continue to pose a significant threat.”

Slow Brew

Starting with its first store in Elphinstone Building in south Mumbai — the Tata’s iconic Bombay House headquarters is just a stone’s throw away — Starbucks has built its business steadily in India. In fact, the chain is behind its initial target of 50 stores — it has 46 operational currently — but has expanded to the National Capital Region, Bangalore and Pune as it seeks to take on CCD.

According to analysts, Starbucks has firmed up its presence as a premium coffee retailer, with some malls even using it as a carrot to attract free-spending consumers to its premises. “Having a Starbucks outlet is a guarantee to attract upscale customers to a mall and this in turn helps convince international labels to rent space there,” says Anand Sundaram, CEO of PPZ, a mall management firm which operates malls nationwide; RCity in Mumbai’s Ghatkopar suburb, for instance, houses a Starbucks store.

A 34-year-old Tata Administrative Services graduate is piloting Starbucks’ business in India. Avani Davda went from being an executive assistant to Tata Group veteran Krishna Kumar to helming the joint venture with Starbucks for India. Having tasted her first Starbucks Coffee in Seattle in 2011 (she counts Sumatra and India Estate Blends as her favourites), Davda thinks the chain has plenty of scope for growth. “India is one of the most exciting markets in the world…we believe we have a unique opportunity to deliver an unparalleled coffeehouse experience to Indian consumers,” she says.

“We firmly believe in our ability to build and grow the Starbucks brand in India and are confident in the opportunities that the Indian market offers for it to become one of the top five markets for Starbucks globally.”

Heady Growth India provides a fertile market opportunity for CCD and Starbucks. According to company executives and analysts, there is plenty of opportunity for growth. Euromonitor says the Indian coffee cafe market will grow from Rs 1,683 crore in 2012 to Rs 2,276 core in 2017.

“Growth of cafes in India is driven by many factors, including favourable demographics, rising income levels, graduation from mid-sized towns [to large metros] and the advent of global chains,” says Sunitha Barlota, a research analyst at Euromonitor International. “Cafes in India are considered a perfect place to socialize among college goers and working professionals.”

Others such as Asitava Sen, head of the food, agriculture research and advisory team at Rabobank Group in India, believe there is plenty of headroom for growth in this space, with cafes just starting out on a sharp growth curve. Sen estimates that there are around 2,000 coffee cafes across India and there is room for 5,000 or more nationwide. “The Indian market

is very different from the West … here a visit to a cafe is more a social occasion and less a quick visit…the opportunity for cafe owners is to try and get a greater share of wallet from these consumers,” he adds.

Starbucks has discovered over the past few months how different it is doing business in India. According to Manmeet Vohra, the Indian operation’s marketing and category chief, they discovered that peak hours in India were 2 pm to 6 pm (compared to 5 am to 11 am in the US, for example) and takeout orders accounted for barely a fifth of their business in India (compared to 80% in the US).

What’s more, as customers spend time in the cafes, they needed to design them differently. So the cookie cutter design gave way to customized spaces in each city — for example its store in Pune uses copper elements, in a nod to the heritage of the city. “After office and home, we want to be the firm favourite as a third place to hang out,” Vohra adds.

According to brand consultant Harish Bijoor, consumers have made their preferences clear — Starbucks is the more upscale hangout, while CCD is a budget option. “Both these brands have strongly defined identities and consumers identify with them,” says Bijoor, who worked for eight years at Tata Coffee (a subsidiary of Tata Global) between 1993 and 2001. By his estimates there are currently 2,350 cafes, while the potential is for as many as 6,440 such outlets.

Success Potion

According to analysts such as Euromonitor’s Barlota, there are three or four key ingredients that determine the success of a coffee cafe. Other than location — CCD’s success to date is determined by being located close to colleges, business complexes, high streets and malls — pricing can be a make or break factor. This is particularly crucial at the lower end of the market where budget-conscious buyers are wary of shifting from cheap restaurants (sometimes called Darshinis) to a CCD or Starbucks. Those that do make the shift and pay the premium can be demanding on quality of service and product.

As consumers make their choices known, there seem to be strong indications that India’s coffee cafe market is going to consolidate. According to analysts, while CCD may be the mass market leader, Starbucks has occupied a strong position in the premium space, with plans to slowly but surely expand its presence. This means others in the market, including Costa Coffee, Baritsa and Gloria Jean’s, will struggle to attract and retain loyal custo mers. As the market gets polarized, CCD and Starbucks are expected to soon dominate the coffee cafe sweepstakes.

Some of these signs of strife are already visible. For example, Barista, the second organized retail chain in India after CCD, is on the market for a third time . While Ravi Deol, the chain’s first CEO, was tipped as a leading takeover candidate, his interest has faded in the past few weeks. Deol couldn’t be reached for comment. Italian owner Lavazza also declined comment.

Then, Costa Coffee, brought into India by Devyani International, is the subject of much wrangling between partners. Devyani, which runs the India business for the likes of KFC and Pizza Hut, has struggled for years with the Costa Coffee business. Virag Joshi, the CEO of Devyani, wasn’t available on the phone and didn’t respond to an email seeking comment.

Costa Coffee, however, doesn’t seem to have given up on India. “Costa is the world’s second largest coffee shop brand and is growing rapidly in its domestic UK market and globally adding over 300 stores a year,” says Kate Manning, a spokesperson for the chain. “We are very much committed to growing our presence in India.” While Costa has some 120 stores in India, she declined to enumerate the firm’s future plans. Costa’s India head, Santhosh Unni, has recently quit.

Third, Gloria Jean’s is also dealing with its own dose of bitter beans, with its joint venture with The Landmark Group on the rocks. Both sides didn’t respond to emails seeking comments, but real estate analysts said the chain was scaling back its presence in costly high-street locations to salvage the business.

However, CCD’s Siddhartha isn’t getting distracted by the woes of the competition. “All foreign coffee brands are looking at the top 5% of the Indian market — i.e. high income group consumers,” he says. “But we are focusing on the dynamic youth population. Roughly 70% of Indians today are below 35, and our goal is to reach out to them.”

Focus Matters

Experts argue that as a scale player, CCD has been able to escape much of the tumult in the sector because it has focused on its core proposition of affordable coffee, with comfortable surroundings, and steered clear of trying to tinker too much with a winning formula.

Experts argue that as a scale player, CCD has been able to escape much of the tumult in the sector because it has focused on its core proposition of affordable coffee, with comfortable surroundings, and steered clear of trying to tinker too much with a winning formula.

This is not to say that it has stood still in an evolving market. CCD, for example, gets around 35% of its business from food — an area it only focused on in the past 12-18 months.

“What stands out about Siddh artha and CCD is their ability to make strategic changes in response to customer demand and competition — expanding the food offerings or rationalizing store count to sustain growth and profitability are great examples,” says Sanjay Nayar, MD and CEO of KKR India.

“There is a great opportunity for CCD to leverage its large network to drive growth in a new direction,” he adds. In March 2010, KKR invested $210 million in Coffee Day Resorts, the holding firm which includes the coffee retailing business.

Venu Madhav, who has been with CCD since day one and got promoted as chief executive over a month ago, says the coffee retailer is streets ahead of the competition in understanding the Indian consumers’ needs.

“Cafes are social hubs, where coffee and conversation play a key role in the success of an outlet,” he says. “India is a value-conscious market and we see ourselves in the affordable luxury category of coffee retail.”

Madhav is keen to expand the reasons consumers stroll into a CCD — not just for a relaxed cuppa but for breakfast, lunch and dinner, too. It’s no surprise that CCDs on many highways are popular rest stops and the chain is focused on expanding its presence in the space.

Brand Battles

CCD is acutely aware that it takes little for consumers to switch loyalties — however good the coffee may be. To try to keep pace, CCD’s interiors are periodically updated to prevent its ambience from looking dated and jaded. “The look of our stores changes completely every couple of years,” avers Madhav.

While CCD continues on its rapid expansion path, Starbucks isn’t rushing to keep pace. According to industry sources, Starbucks could add a dozen or more outlets in the next year in India and is looking to expand its presence in the cities it is present in and consider going to second-tier metros, too.

“Each market comes with its own set of opportunities and challenges and our guiding principle across all markets continues to remain the same: to inspire and nurture the human spirit — one person, one cup and one neighbourhood at a time,” says Davda. And in the process she’d be hoping Starbucks coffee becomes most Indians’ cup of tea.

source: http://www.articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com / The Economic Times / Home> Industry> Services> Retail / by Rahul Sachitananad & K R Balasubramanyam, ET Bureau / June 08th, 2014