By Richard Lasrado [ Published Date: January 29, 2012 ]

As I keep recalling the great personality I had met a few times, esp., for an interview as a budding journalist way back in 1974, the picture gets etched in the mind, deeper and deeper.

The Grand Old Man of Kodagu (then Coorg), Kodandera Madappa Cariappa (January 28 1899 – May 15, 1993), then a retired General, who was an epitome of discipline, punctuality and promptness, had graciously consented to my request to be interviewed for an Indian journal.

He, as independent India’s first and until then only Commander-in-chief, had retired in early 1952. He was made an honorary Field Marshal only later, as late as in 1986, during prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure.

A couple of kilometres down the serpentine road from Mercara, now Madikeri, to Siddapur stands the palatial ‘Roshanara’, the residence of the great man.

My nervousness was showing. Being a cub journalist, I was to meet a great warrior of world status and a hero of the world wars, who had been honoured by presidents, kings and heads of states.

Led into his drawing room by an attendant, I was awe-struck by the splendid display of military trophies, mementoes and souvenirs.

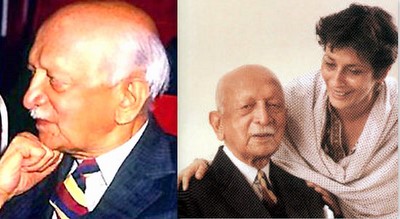

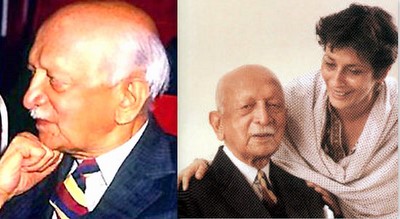

Field Marshal with his daughter Nalini

Two minutes after the appointed time, the broad-shouldered, six-foot-plus celebrity with peach-pink complexion appeared on the scene. As said already, it was not the first time that I had seen or heard him. But his simplicity and friendly nature were absolutely heart-warming and disarming at the same time. To cap it all, when the General repeatedly apologized for the two-minute delay with folded hands, I was rendered totally speechless and blank, for a moment making me forget the questions I had long planned to shoot.

Our meeting was scheduled to last just about an hour. But as the clock ticked away, the General seemed to be interested and asked to go on.

Reminiscing about that interview I had almost forty years ago invariably necessitates the quoting of some words of his, which, over the years have proved prophetic.

The following excerpts from the interview may provide an insight into his personality and thinking. They should be appraised only in the light of circumstances that prevailed in India in the early 1970s. Those among the readers who may have closely followed the India’s developments since 1970 may find his words quite fascinating.

******************

On the prospects of a military government in India and if such a measure would cure the country of all its ills and ailments.

The moment I mention a military rule, I am misunderstood. I would say, military rule can never take over India. One, we are a huge country and are beyond the control of a military machine. Two, we have too many diversities to keep us together. Three, when our defence resources are engaged at the borders, they may not be equipped to rule the country.

It makes me sad to see the inroads of foreign ‘isms’ into our body politic and havoc they have wrought. But democracy is deep down in our blood. Yet, under the present conditions, an indefinite President’s rule all over the country would do us a lot of good. Only such areas as may be unruly can be given in the hands of the army. Only after restoration of normalcy can elections be held.

The President can draw on the best talent in the country and form a cabinet of intellectuals and run the affairs of hte state more efficiently.

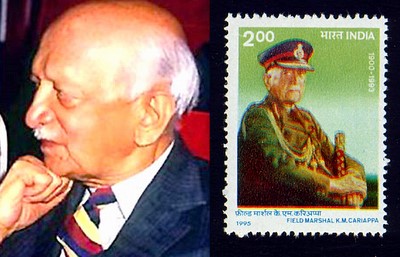

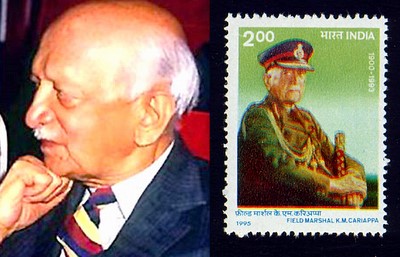

Commemorative stamp issued in his honour

On Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement against corruption in Bihar and elsewhere.

It is comforting to know there is a clean and upright person like JP to show us the way. But the public opinion is not strong enough in our country. People might curse the leader and the government. But in private the same persons run after politicians for licences, permits and favours.

Matters have come to such a dangerous pass that corruption is almost being regards as a way of life. Today’s students might call the politicians corrupt, while they indulge in copying and toehr malpractices themselves. It is just like a pot calling the kettle black.

On the future of the opposition parties and if the newly-formed Bharatiya Lok Dal (BLS) would be a mess or a Messiah?

A steam-roller of the ruling party anywhere poses a great danger to democracy. Presence of a plethora of political parties aggravates the situation.

All along, I have been advising all opposition parties to sink all their ideologies and come together on four major issues – 1. Defence of the country, 2. Foreign policy, 3. A realistic economy and 4. Internal security.

I can only say that the formation of BLD is a healthy democratic development, but how how far it is going to be a success, only the future can tell.

On the future of sports and games in India – he was a spin bowler, and a tennis and hockey player himself.

Sports is in our blood. Yet our achievements are not up to the mark. The main reason is the lack of practice as well as the grace to accept defeat. Dedicate practice is a must.

On India’s dismal failure in the field of hockey in spite of having a staggering line-up of talent.

There could be many reasons. But I would like to blame it on the lack of practice in the first place. Matters have been made worse by the ubiquitous ‘politics’. I did my best to keep this menace at bay during my tenure as three years as chairman of the All India Council of Sports (AICS), but it was in vain.

**************

I had two more issues that I wanted to broach with him. With much diffidence and hesitation, I took courage to ask him. First was about a little-known and little-publicized episode between him and Mahatma Gandhi. There was a brief pause.

Obviously, many had hesitated to put this question to him. He said, ‘Your way of asking such questions reminds of Melville de Mellow of All India Radio, who was here to meet me a few days ago.’ I was lost for words as my jaw dropped.

Then he handed me the Mahatma’s biography by Prarelal, who has devoted a whole chapter to this particur incident. The General felt that I would be better off with a third-person account than his own version.

Soon after the Indian independence, Cariappa had thundered at a metting in London that in the then-prevailing circumstances, the concept of Ahimsa (non-violence) was not going to be any help to India and a powerful army alone could make it one of the strongest nations in the world.

Gandhi was indignant at this candid outburst and shot back a rejoinder in his journal, ‘Harijan’, saying that even Generals greater than Cariappa would admit that they had no right to talk on non-violence. The concept of non-violence alone could eliminate the causes and chances of wars, wrote the Mahatma.

The General wanted to clarify matter with the Father of the Nation. They did not know each other personally and so he sought an audience. In December 1947, in full military attire, he visited Gandhi in Delhi.

It was a day of silence for the Mahatma., who was spinning his celebrated charkha. The General left his shoes behind, entered the room and saluted Gandhi. He told him that he had come to seek his blessings. Declining the chair offered by Gandhi, he preferred to squat next to him.

Bapu broke his silence and asked Cariappa if he had read the article in ‘Harijan’. Cariappa answered in the affirmative and humbly said that he felt honoured by Gandhi’s reference to his speech, all the more because he had commented on someone who he had never met before.

Then he went on to clarify that the soldiers’ community was the one that bore the brunt on many counts. They too believed in non-violence. If at all thre was a community opposed to wars, it is the soldiers’ community, he said.

Cariappa continued as Gandhi heard him with rapt attention: Soldiers did not like wars, not so much for the dangers and risks they were fraught with, but because they were aware of the futility of war in solving disputes and problems of the world. If at all soldiers fought wars, they did it as a mandate of the people. If people did not want wars, they should tell their governments so; it that didn’t work, they should change their governments. Gandhi looked impressed with the stream of thought and said he needed time to think it over.

Two days later, they met again and conferred on the same subject. On January 18, 1948 they met yet again in Birla Bhavan, Delhi. The General had come to bid good-bye on his wasy to Jammu-Kashmir action mission and seek his blessings. The Mahatma expressed the hope that the problem would be solved by peaceful and non-violent means, and asked Cariappa to report to him about his mission thereafter. The General said he would certainly do so.

By a strange quirk of fate, on January 30, 1948, the General returned to Delhi with the sole purpose of meeting the Mahatma, only to pay his last respects to the latter’s mortal remains at Raj Ghat.

====

The second question was also sensitive. I could sense a tinge of sadness and bitterness when he replied to my query. It was about the only only political shot he took by contesting a southern Mumbai – then Bombay – Lok Sabha constituency sometime in 1971.

I enquired of him as to why he had to contest from there and earn a needless tag of being a Shiv Sena candidate, although he was being supported by seven different parties, including the Bharatiya Jan Sangh and the Swatantra party. Instead, he could have contested from south Mangalore constituency which included his own home district of Kodagu, I said.

He replied: ‘ When I contested, my manifesto was simple and plain – giving priority to people’s basic needs of food, clothing and shelter and education, strongly opposing luxury life, control over pompous offices, conference and foreign tours, instilling a national feeling in everyone instead of narrow parochial and linguistic atttitude.’

I decided to contest in certain circumstances. At 71 then, I had no ambition or craving for power. One day, Congress (O) leader former railway minister Poonacha called me up and said the his party’s high command had chosen him to be their candidate. All opposition parties were to lend me their support. Hence I had to consent, he said. I thought to myself, just like General de Gaulle reached the top with military experience behind him, that I could raise my voice in the parliament at least for ex-Servicemen and thought this could give me a suitable opportunity to fight for them.

I told Poonacha, ‘ I am an VOP – very ordinary person. I do not have the resources to fight the election.’ He told me not to worry, assuring that all the parties would take care of it. However, a few days later, Poonacha called again to tell me that the party had instead chosen himself instead of me. Anyway, I said it was OK.

Another few days later, I received a telegram from the Swatantra party leaders informing me that 6 or 7 parties had chosen me as their joint candidate from southeast Bombay constituency. Shiv Sena happened to be one of them. I had a formidable Congress candidate like A G Kulkarni against me. Yet the mood was so upbeat that my victory was thought to be easy. There was even a talk going around that in the likely coalition government in Delhi, my name was thought to be the right one for the defence portfolio.

Yet I lost. Former president V V Giri once met me after the election and enquired why I lost when the chances were bright. Without mincing words, I told him, ‘One of your own central leaders came down and started saying that Cariappa was a Kannadiga and a southerner should not win in Maharashtra’ and such other narrow-minded words. There were twelve horses in the race. Jan Sangh and a few others let me down in the middle. Jan Sangh termed me pro-Muslim since I refused to attend the Vishwa Hindu Parishat programmes. Bombay Kannadigas alienated me saying that I was a Shiv Sena candidate. I called all representatives and tried to clear the misunderstanding in the presence of a Swamiji from Udupi, but it was of no avail. I fell a victim to adverse propaganda.’ Giri seemed to agree with in full.

*************************

Cariappa was a no-nonsense, no-compromise personality. There have been cases of chiefs of service staff, as they approached retirement, having tried to appease the centres of power with an eye on plum posts like those of ambassadors, governors and the like. Many retired officers have taken up adminstrative posts in corporate houses. But this intrepid fighter stood above all that. He kept on raising his voice against misrule, corruption and political chicanery.

During his tenure as India’s high commissioner to Australia and New Zealand between 1953-55, an off-the-cuff remark against the racial policy of the Australian government is said to have created a diplomatic row, which created a rumpus in the Indian parliament seeking his recall. But he stood his ground, without any fear.

His differences of opinion with the Nehru-Krishna Menon combine was a matter of an open secret. During Indira Gandhi’s rule, once he had advocated handing over of disturbed areas to the military. Politicians sought his arrest on charges of giving a call for military rule. They even demanded withdrawal of his pension.

Those were the days when a late prime minister used to blame the ubiquitous ‘foreign hand’ or the ‘CIA’ for most of the problems in the country. Cariappa did not hesitate to ridicule it saying that a day would come when the prime minister’s chest pain would be blamed on the CIA.

Naturally, he had earned the displeasure of the ruling classes. No wonder, he was not recognized until late in his life. Gen Sam Manekshaw was upgraded as Field Marshal soon after the Bangladesh war victory in 1971.

The very fact that a man like General Cariappa, who had served the Indian army for a good 33 years, was made an honorary Field Marshal 33 years after his retirement during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure as PM, speaks of the vagaries and systemic malaise that plague our country.

Field Marshal Cariappa always said he was an Indian first, and a Kodava or Kannadiga only next. He played a major role in getting the names Mercara and Coorg changed back to their ethnic forms as Madikeri and Kodagu. He also had fought against the Kambadakada dam project which would have gobbled up thousands of acres of fertile land of Kodagu.

His residence ‘Roshanara’ and a lifesize statue at a circle on the way to Mysore stand majestically in his memory. A college in his hometown has been re-named after him.

When the messenger of death came calling in a Bangalore hospital in 1993, for sure, he mght have struggled to take away this giant, the fearless soldier who may have said good-bye to this world with sadness. Because the India of his dreams is still a long distance away.

If power lay in the hands of patriots and upright Indians like Field Marshal Cariappa, it would have been a different picture. Maybe his dream may come true some distant day, but, alas, there cannot be another Cariappa.

source: http://www.Mangalorean.com / by Richard Lasrado / January 29th, 2012