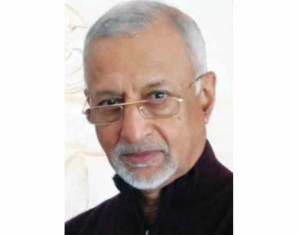

Professor Lissie Mathew’s book, Kathivanoor Veeran: Malakayariya Manushyan, Churamirangiya Daivam, traces the evolution of an ordinary man to God

Mannappan and Chemmarathy were not exactly a model couple, they fought as intensely as they loved. When he dies in war, after a domestic squabble, Chemmarathy is heartbroken, the last words she uttered to him were the unkindest. She jumps into his pyre and the two attain godly status. This is an extraordinary tale of Mannappan, a man who goes up to Coorg in Karnataka from his village, Mangad in Kannur, dies a war hero, and returns as Kathivanoor Veeran. To this date, few can listen to the tragic hero’s tale without a lump in the throat.

Professor Lissie Mathew’s book, Kathivanoor Veeran: Malakayariya Manushyan, Churamirangiya Daivam, retraces Mannappan’s journey to Kodagu (Coorg). Having grown up in Vayattuparambu in Kannur, Lissie’s childhood was full of the stories and colours of Theyyam. And she had always wanted to explore the story of Kathivanoor Veeran. A professor of Malayalam at the Sankaracharya College, Kalady, working on its Payyannur campus, she has to her credit 12 books.

Kathivanoor Veeran is one among the most popular Theyyams, for it is a visual spectacle where the performer indulges in acrobatics and comes in close contact with fire. “It is an experience to watch Kathivanoor Veeran in action. I wanted to bring out the hero’s story through this book,” Lissie says.

The book delves into the micro-histories of Northern Malabar, where folktales, fiction, fact and history mingle in curious ways. It also explains the Theyyam, its rituals and practices in a detailed manner.

Excerpts from an interview with Lissie Mathew

Can you describe your relationship with the work.

I should say the book came out straight out of my mind, though it took four years of research, travel and interaction with people, to complete. It was hard work, but I wanted to trace Kathivanoor Veeran’s route from Mangad in Kannur to Kodagu (modern day Coorg). Through the thottam (the song sung before the ritualistic practice), which describes Mannappan’s life and death in great detail, one can get an insight into the geography, culture, mores and history of North Malabar. I followed the thottam to retrace Mannappan’s journey.

The thottam would have been difficult to interpret as it is in archaic Malayalam, often in the local dialect.

Yes. I could not understand it, the first time I heard it. I got the thottam singers to sing it for me, recorded it and I listened to it over and over again, until it began to make sense. It is fascinating, how these songs combine legend, history, reality and imagination. Most of the places mentioned in the thottams remain, though in different names. These thottams speak of a culture that is over a 1,000 years old.

What is the relevance of Theyyam today?

Theyyam talks about people and their problems, their relationship with Nature and fellow creatures. A rural-agricultural lifestyle makes up its very foundation. For instance, a Kathivanoor Veeran Theyyam performance is always followed by an annadanam (feast), which everyone partakes of. In this day and age, when we, as a people are becoming more self-centred, this is an example of how we are a part of our community and how we need to share our resources.

Performed most often in sacred groves (kaavus), it is important to understand the relevance of preserving these pockets of biodiversity intact. It is heartening to see that even the younger generation respects the rituals associated with Theyyam. By wanting to preserve the sanctity of Theyyam’s rituals, they are also contributing towards preserving the ecosystem.

Theyyam is performed by people in the subaltern communities. The Chirakkal Kolathiris, the rulers of the land, gave certain subaltern communities the right to perform Theyyam and it is continued to this day. Once they become Gods, even the upper castes, pray to them.

In that sense, Theyyam is undoubtedly, extremely relevant today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books / by Anasuya Menon / February 28th, 2019