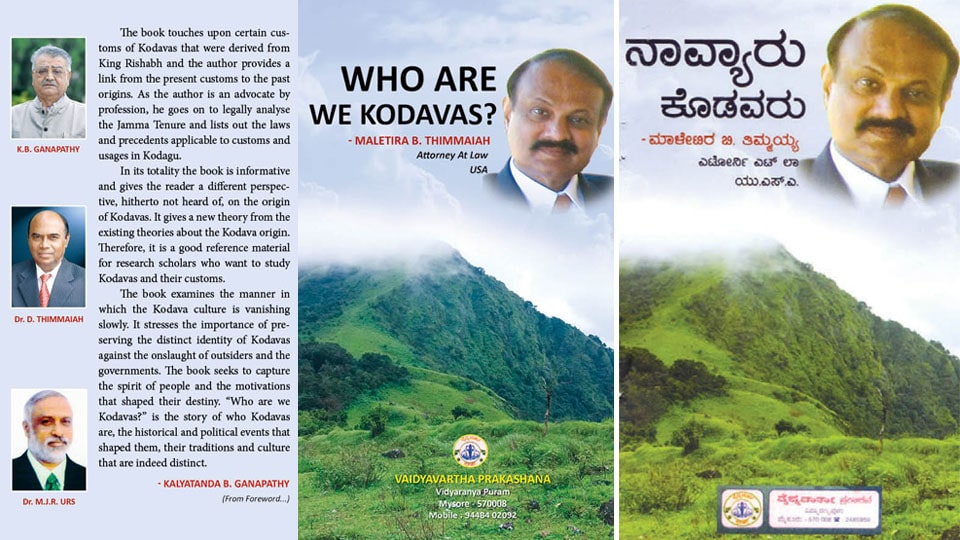

D.M. Trust has organised a function at Rotary Hall on JLB Road here tomorrow (Nov.25) at 5 pm to release the books ‘Who are we Kodavas?’ (English) and ‘Navyaaru Kodavaru?’ (Kannada), written by Maletira B. Thimmaiah, Attorney-at-Law, USA.

Star of Mysore Editor-in-Chief K.B. Ganapathy will release the books. City advocate J.M. Aiyanna will preside. D.M. Trust President Dr. D. Thimmaiah, Joint Commissioner of Commercial Tax, Shivamogga, H.G. Pavithra and Vaidya Vartha Prakashana Founder-Director Dr. M.G.R. Urs will be the chief guests.

Published by Vaidya Vartha Prakashana, the English version of the book has 84 pages while Kannada edition has 80 pages, both priced at Rs.50.

Here we publish the Foreword to the book by Kalyatanda B. Ganapathy, Editor-in-Chief, Star of Mysore and Mysooru Mithra:

This is a book about the people of Kodagu, the land inhabited by Kodavas with their own distinct identity recognised and recorded in history as unique. Written by Maletira B. Thimmaiah, Attorney-at-Law, Staten Island, New York, United States of America, the book traces the origin of Kodavas, their customs, rich history of more than 5,000 years and how a land of such uniqueness was being systematically ravaged by invaders, modern laws and urbanisation thereby depriving the future generations of the rich natural beauty and more importantly the environment.

From time immemorial, Kodavas, with their unique folklore culture, have shown affection, tolerance and respect towards the people who helped them regardless of the communities they belonged to. Showing their gratitude in the form of providing them space and work, Kodavas still regard their guests as God — ‘Athithi Devo Bhava’ and perhaps this attitude has cost them dear when it came to preserving their culture, language and properties.

Supported by extensive research on history, religious books, encyclopaedia, customs and physical features and himself as a member of Kodava community, the author Maletira B. Thimmaiah traces the origin of Kodavas and their customs from ancient times. Kodavas must prepare the future generation to stand tough in defending their heritage against intrusion of outsiders. And to stand firm against outside influence and lobby, each Kodava must know his/ her origin, he writes.

According to the author, the first advent of human habitation in Kodagu is prior to 3000 BC. Rishabh, a ruler from Magahada, abdicating the throne as King of Ganges Valley Civilisation, shared his kingdom among his 100 sons, renounced everything and travelled to Kodagu, then called ‘Kutaka’ in Sanskrit and named it ‘Kudaga’ in ‘Pali’ and other South Indian languages called ‘Prakrits.’

While the first son of Rishabh named Bharat ruled northern half with Ayodhya as capital, the second son Bahubali ruled the South with Paudanapura as capital. The rest of the 98 sons of Rishabh were given different kingdoms. The final fight between Bharat and Bahubali took place in the south and the battle resulted in Bahubali renouncing his kingdom. Later, all the sons of Bahubali went to Rishabh who lived in ‘Kutaka’ for advice. This was how an uninhabited Kodagu became the place to live for North Indian Ganges Valley people.

According to the author, Rishabh believed in ‘Shramana’ school of thought that did not have God, Soul and Creation and where the philosophy of procreation dominated — human being is procreated by his parents and in turn, parents were procreated by their parents. Thus ancestors were the reason or ‘Karana’ (cause) for the continuity of generations to generations. Explaining this theory, the author draws similarities with Kodava customs where families still worship the ‘Karana’ and ‘Gurukaranas’.

The book then touches upon Hinduism and argues how Kodavas do not belong to Indus Valley Civilisation but Ganges Valley Civilisation. Elder-oriented or elder-centric customs and practices existed in Kodagu before the advent of Hinduism to India. Priests were not involved in Kodava traditions in any manner with a major role played by elders or village ‘Thakkas’. Brahmins had to work under the ‘Thakkas’ and they did not have any supremacy. As such, Brahmins felt belittled and ignored. Hence they considered Kodavas as descendants of Kroda King, born to a ‘Shudra’ woman who was low in caste (according to Hindu caste system) and was unchaste. They called Kodavas as ‘Ugras’ and said the name Kodava was derived from Kroda king.

The book argues that this was the revenge of Brahmins or the priest class against Kodavas who did not allow them to their ‘Ainmanes’, ‘Kannikombare’, ‘Kaimada’, festivals, marriages and other auspicious ceremonies.

The author then traces Lingayat religion and kings who influenced Kodavas. Kodavas were pitted against Kodavas. They killed each other while the Lingayat Rajas watched the fun. Then came Islamic invasion led by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan where Tipu converted a large number of Kodavas into Islam and massacred those who did not comply with his orders.

Next came the Britishers who introduced coffee. They tricked Kodavas to part with their Jamma lands to cultivate coffee and institutions like “Consolidated Coffee Estate” was born. The book describes how the British exploited Kodavas to serve their own interests in India and world over. The physical strength and bravery of Kodavas were well used by the British and moved many Kodavas from paddy fields to war fields. While a few got acclimatised, many Kodavas died unnoticed and unsung. The British even imposed heavy land revenues and brought in land laws for their advantage. Some of the unjust and illogical regulations introduced by the British continue even today even after Kodagu State was annexed into Karnataka.

After the British rule, the elected governments, with ignorant and self-centred lawmakers, brought in more restrictive laws without understanding the ground realities. This was done with no representative from Kodagu while framing such rules. Many land laws have been questioned in the Court of Law. The book illustrates how Kodagu has become a looting place for outsiders since independence. The laws enacted by Karnataka government like Land Revenue Act, Forest Act, Management of Reserved Forest Rules and land tenures have dealt many fatal blows to Kodava customs, traditions and land holdings, says the author.

The book touches upon certain customs of Kodavas that were derived from King Rishabh and the author provides a link from the present customs to the past origins. As the author is an advocate by profession, he goes on to legally analyse the Jamma Tenure and lists out the laws and precedents applicable to customs and usages in Kodagu. Probably the author is unaware of the fact that Jamma tenure is no longer existing since 2011 following an amendment to the Karnataka Land Revenue Act, 1964.

In its totality the book is informative and gives the reader a different perspective, hitherto not heard of, on the origin of Kodavas. It gives a new theory from the existing theories about the Kodava origin. Therefore, it is a good reference material for research scholars who want to study Kodavas and their customs.

The book examines the manner in which the Kodava culture is vanishing slowly. It stresses the importance of preserving the distinct identity of Kodavas against the onslaught of outsiders and the governments. The book seeks to capture the spirit of people and the motivations that shaped their destiny. “Who are we Kodavas?” is the story of who Kodavas are, the historical and political events that shaped them, their traditions and culture that are indeed distinct.

‘Who are we Kodavas?’ by NRI Kodava to be released in city tomorrow

source: http://www.starofmysore.com / Star of Mysore / Home> News / by November 24th, 2018