Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David is among some famous paintings that are commonly seen in Army Messes

The portraits, paintings and caricatures commonly seen in the messes across arms

“His eyes were brown, dark brown.”

That was a detail missing from the image I had received on my phone; it was a pencil drawing.

“His moustache would cover the upper lip,” said the next message. “Couldn’t see the shape. So, only the eyes are left.”

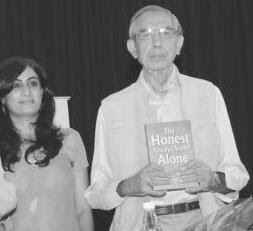

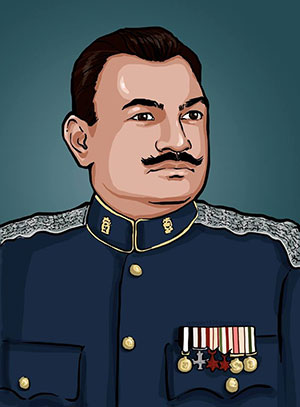

I looked at the picture again. A handsome man in his military uniform, two stars and an Ashoka emblem on each shoulder, surrounded by a buff passe-partout, sporting a mustachio markedly niftier than my memory of it. His name tag read: C T Somaiah.

Colonel C T Somaiah

I was on WhatsApp with his wife, Indra, discussing his portrait for this article. She is a naturally indulgent person and, at seventy-four, has perfected the art of generosity. Notwithstanding the questionable shape of the facial hair, she said she liked the sketch. “It brings out the essence, somehow.”

The sketch was a memento, presented to the late Colonel Somaiah by one of the two Air Defence regiments he commanded. It was a replica of his likeness that hangs in its Rogues’ Gallery.

Rogues’ Gallery. The term carries not-so-reputable connotations. Traditionally, it stood for a collection of mugshots of criminals, used by the police to identify suspects. The name is also familiar to DC fans: a group of supervillains that Batman has had to face over the years.

But the Rogues’ Gallery I am writing about features heroes.

In a military setting, it is meant to highlight the Commanding Officers, a.k.a. Tigers, of a unit. A set of portraits, typically photographs, is displayed in the office of the incumbent CO. Another set of pictures may be found in the Officers’ Mess.

The very nature of a Rogues’ Gallery evokes esprit de corps. The greatest binding force in the Army is unit cohesion, and the two institutions by which we can gauge discipline and standard are the Quarter Guard and the Officers’ Mess. The Quarter Guard is where the guidon — a flag or symbol used to represent the unit — is housed, and is the most important establishment in the unit lines. For the purpose of this article, we will focus on the Mess.

Wedded to the Olive Green — a book considered to be the vade mecum for Army wives in India — has this to say: “As an institution, it has a great influence on an officer’s life… The customs and etiquettes, which are observed, are essential for fostering pride in the Service.”

The Mess, however, is one of the most misrepresented elements of Army life in popular culture, especially cinema. The glamour — the uniforms, the legends, the mythology — proves too much to resist, and filmmakers end up depicting a fantasy world with ballroom dances and designer gowns.

Some of the films guilty of such distortion are Hum (1991), Sainik (1993), Pukar (2000), Ab Tumhare Hawale Watan Saathiyo (2004)…the list is long. Even sensible directors like Vishal Bhardwaj and Mani Ratnam couldn’t help going over the top in 7 Khoon Maaf (2011) and Kaatru Veliyidai (2017), respectively. Films that fare much better on the authenticity scale are Prahaar (1991) and Lakshya (2004); we could add Govind Nihalani’s Vijeta (1982) to this list, but it is an Air Force film, not an Army one.

Caricatures

So, what makes an Officer’s Mess “real”?

“The Mess should be martial,” said Kuki Bawa, one of the most pukka Army ladies I know. “It must have a lot of wood, brass, and, of course, silver. Maybe some leather as well.” Jutimala Thakur, another accomplished memsahib, added vintage paintings to the list.

Some famous paintings that are commonly seen in Messes across arms are Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David, Collision of Moorish Horsemen by Eugène Delacroix, and The Combat of the Giaour and Hassan, also by Eugène Delacroix.

Then there are paintings that are specific to a battalion or regiment. “No Bengal Sappers Mess is complete without The Storming of Ghuznee Fort,” said Shabana Chowdhury Ali. As a First Lady, she has a significant role to play in matters of Mess décor. “Sensibilities are changing,” she explained. “A lot of the artwork in our Mess comes from travels of officers and veterans.”

Collision of Moorish Horsemen by Eugène Delacroix

The Combat of the Giaour and Hassan by Eugène Delacroix

Most such paintings are reproduced at Mhow, Meerut, and Kolhapur, according to artist and fauji wife Monika Tomar Saroch.

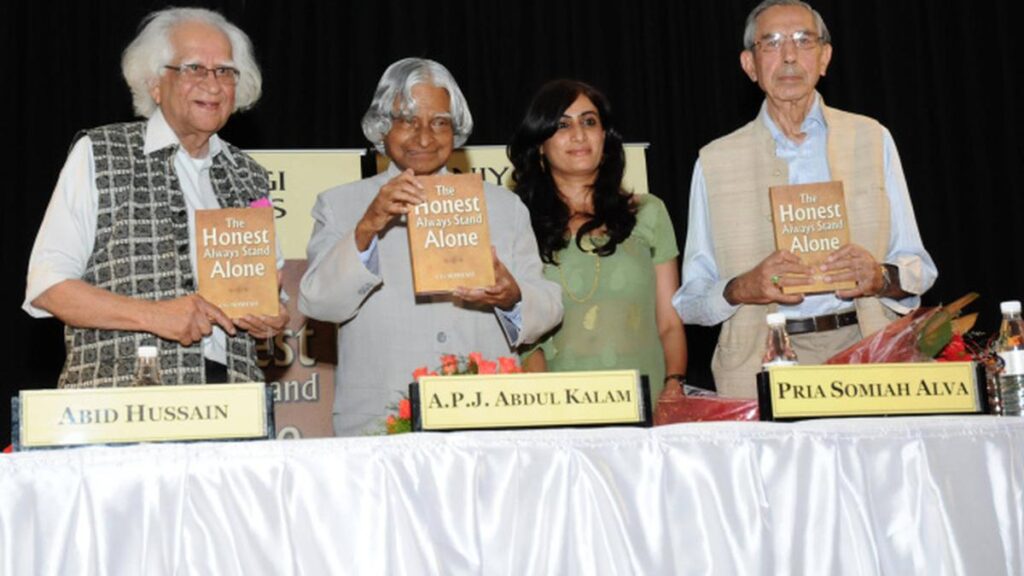

Monika was commissioned by her husband’s unit to make thirteen portraits for its Golden Jubilee of Raising. She was given oil portraits as a reference, and she replicated them in pen-and-ink. It took her about a week to complete each picture.

“What do you keep in mind while making these portraits?”

“For me, the character has to come out,” she replied. “How he was as a CO.”

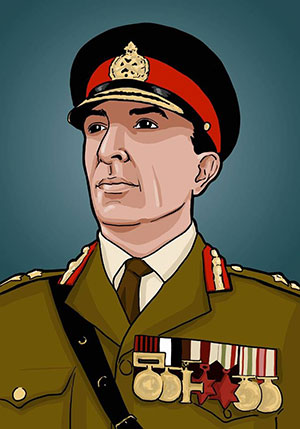

Illustrator Maryam Hasan Ahmad said she looks for the most defining feature of a person. “Also, I have to be very particular about the uniform. I cannot go wrong with hard-earned medals.”

Maryam was a new bride when she saw a Rogues’ Gallery for the first time eighteen years ago. “It was a dream of mine to make my husband’s pencil sketch when and if he took over command. And my dream did come true, Alhamdolillah!”

Maryam has since made portraits for many regiments, also experimenting with canvas prints.

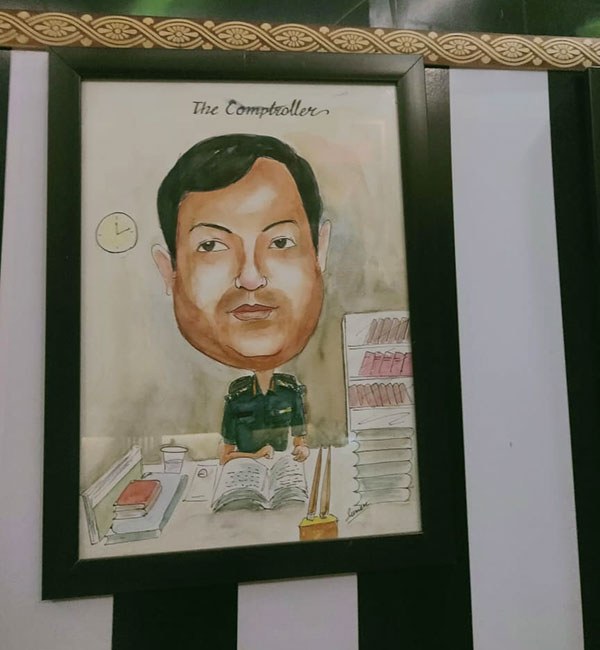

The bar in an Officers’ Mess is where one can see more such inventiveness. At one Mess, I saw caricatures, complete with playful captions: The Connoisseur, The Meditator, Scholar Warrior, Top Gun… The Commanding Officer wanted something quirky for that space.

A former CO — who wants to be identified simply as “a senior veteran who had the privilege of leading his regiment” — said that whatever the occasion or constraints, a Mess should be grand enough to make a visitor’s jaw drop. “But a Mess is not a five-star hotel. And it certainly isn’t a boudoir with floral curtains and valances.” He reiterated that the Mess is one of the bedrocks of a unit, and its folklore and traditions must be carefully documented.

Portraits made by illustrator Maryam Hasan Ahmad

During his tenure as a CO, he had enlisted the skills of a gifted soldier to sketch a picture of his predecessor. He had also commissioned two portraits in oils to commemorate the achievements of unit officers.

One of those paintings features a much-admired officer who was awarded the Sena Medal as a young Major. I wrote to his son, a high school student with a strong sense of history, to ask him how he feels when he sees that portrait.

“I am really glad that the unit duly honours its gallantry awardees,” replied Raunaq Singh Bawa. “It is also very heartening to see his portrait alongside the other Tigers of the unit. I feel really proud.”

As I scrolled on my phone to download Colonel Somaiah’s image, I wondered if his wife felt the same way. Mrs. Somaiah called before I could tap on Save.

“You know, Sahana?” she revealed, “This is the only picture of his that I have kept on display. Sometimes, when I am alone, I like to just stand there and gaze at him. I see only his eyes. They talk to me.”

source: http://www.thepunchmagazine.com / The Punch Magazine / Home> Non Fiction – Essay / by Sahana Ahmed / September 30th, 2020